Pope Francis, Br. Guy Consolmagno and the Vatican Observatory Team © Vatican Observatory

“God is the reason I do science”

Br. Guy J. Consolmagno, S.J.

Being the Director of the Vatican Observatory and the Specola Vaticana as well as the President of the Vatican Observatory Foundation, Br. Guy J. Consolmagno is a member of the 'Societas Jesu', the Jesuits, the largest religious order in the Catholic Church. And a philosopher. At the same time, he is a studied scientist: the IAU honored his work with the naming of asteroid 4597 Consolmagno. It stands to reason that in his numerous publications he also deals with the question of whether and to what extent there is a contradiction or conflict between biblical content and scientific findings.

We look at the world through the eyes of religion or through the eyes of science: what is the difference? What do we see? What questions are we confronted with?

I only have one set of eyes.

When I look at the world, I constantly interpret what I see in terms of what I expect to see, while understanding that I need to be aware of – I need to be ready to be surprised by – things that I see that I didn’t expect to see. And those expectations are based on the assumptions I make about how the world works – scientific and philosophical and religious assumptions that are constantly being updated as I see, and learn, new things.

Those assumptions are a whole big ball of hopes and fears and expectations and prejudices and dreams! They are shaped by my personal history. And they are distorted by all the things that are not in my history; I would certainly see the world differently if I had been raised in Africa, say, rather than America.

Of course, trying to analyze how I see the universe is like trying to analyze love. Or a good joke! It’s like trying to understand a frog by dissecting it. You will know how all the parts fit together, but you lose the experience of the squiggly little green animal; you wind up killing the frog.

Yes, I see the world as a member of a religious order. I would see the world differently if I had been married and raised a family; that’s a set of experiences I will never have. But likewise no married person can know from the inside what it’s like to live a life of celibacy. And that’s no different from saying that because have I spent my life studying planets, I can never have the same intimate knowledge of, say, microbiology.

Instead, what we do both as scientists and as religious people is to pay attention to the larger community of people who have experiences that I haven’t had. I don’t try to do every experiment in science on my own. Likewise, I don’t depend only on my own religious experiences. My eyes are turned not only outward to the stars, or inward to my own spiritual life, but also to the other people around me who can take me to places I would never get to by myself. (And they can give me a heads-up if they think I am going wrong.)

The Vatican Telescopes VATT © Paul Schulz

Love is not an exercise with an answer in the back of the book

Vice versa: How do you manage to relate science and faith to each other?

The misconception I want to dismiss is the idea that science and faith are separate. I believe in science, I have faith in science. Every rational argument has to start with axioms, assumptions, basic points that you take on faith. And I want my beliefs, scientific or religious, to be based on experiences. Data, if you will. Every religious expression begins with a religious experience.

But let’s turn this around and ask a different if related question. Why do I bother to try to experience science or faith? Why do I bother to make assumptions and then reason from those assumptions? I study the universe because I love it. I practice my faith because it gives me a way of expressing love to God.

Love is not an exercise with an answer in the back of the book. When it comes to questions of love, there are certainly wrong answers, but there is never one right, final, answer.

Now, one of the interesting tenets of my faith is the idea, explicitly expressed in our scripture, that God is love. So the reason that I do science is because I find God in it when I love it. And our scripture also tells me that God is truth. So the science that I pursue only works if it is in the pursuit of truth (rather than, say, the pursuit of tenure or a Nobel Prize) … which is to say, the pursuit of God. So you see, God is the reason I do science.

There are some scientists who say they don’t believe in God. What they really are saying is that there are versions of God that they don’t believe in. And that’s fine with me; there are plenty of versions of God out there that I don’t believe in, either. As I say, there can be wrong answers … even as I admit there is never a single completely right answer.

More often, scientists who do not practice a religion would call themselves “agnostic”. As Carl Sagan once said (to a student of his), “an atheist is someone who knows more than I do.” But of course none of us know for certain. Yet it is hard to do science if you don’t believe in truth. And you’re not likely to want to do it if you don’t love it.

Science is the experience; love is the experience; faith is the experience. None of them are the goal in and of themselves. That’s what Pope John Paul II was saying when he wrote (in Fides et Ratio) that “faith and reason are like two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth.” The goal is neither faith nor reason; faith and reason are the tools. The goal is truth.

Br. Guy Consolmagno with students at the Specola Visitor Center, Castel Gandolfo © Vatican Observatory

Humanity – whether in the stories of the Old and New Testaments or in the facts of science – is always in search of truth, the one and only truth. But truth and truthfulness seem to require provability.

I would like to ask you to elaborate on two aspects that you mention in your dialogical book “Would you Baptize an Extraterrestrial?” together with the Jesuit priest Paul Mueller: Firstly, you take your readers mentally to a famous art museum – to illustrate that there are many ways of depicting “the reality”. Secondly, you formulate that it is about the work of an acting God in a universe “that is governed by inexplicable natural laws”.

One of the great things the Jesuits made me do was to study philosophy for a couple of years – including the philosophy of science. What you say here echoes a 19th century philosophy of science called “logical positivism” which too many scientists think describes what they do, even as they actually behave in very different ways. And logical positivism is pretty much an exploded theory. One of the first things you can do with that philosophy is to show that it isn’t true! Which is to say: starting with its own assumptions (see above about the role of assumptions) you can realize that it is not self-consistent.

Proofs always begin with axioms, assumptions. (See Gödel’s Theorem.) Change your axioms and you can “prove” almost anything! That’s why there are so many different ways to depict reality. And that’s why we talk about natural laws that are inexplicable.

That’s why truth is so elusive. And the genius of science is precisely that it is not looking for timeless truths, but rather the “best description we can come up with at the moment” of those natural laws – which is quite a different thing from a timeless truth. But of course that’s also why science never runs out of things to study, since we know that our best explanation today will always be subject to improvement.

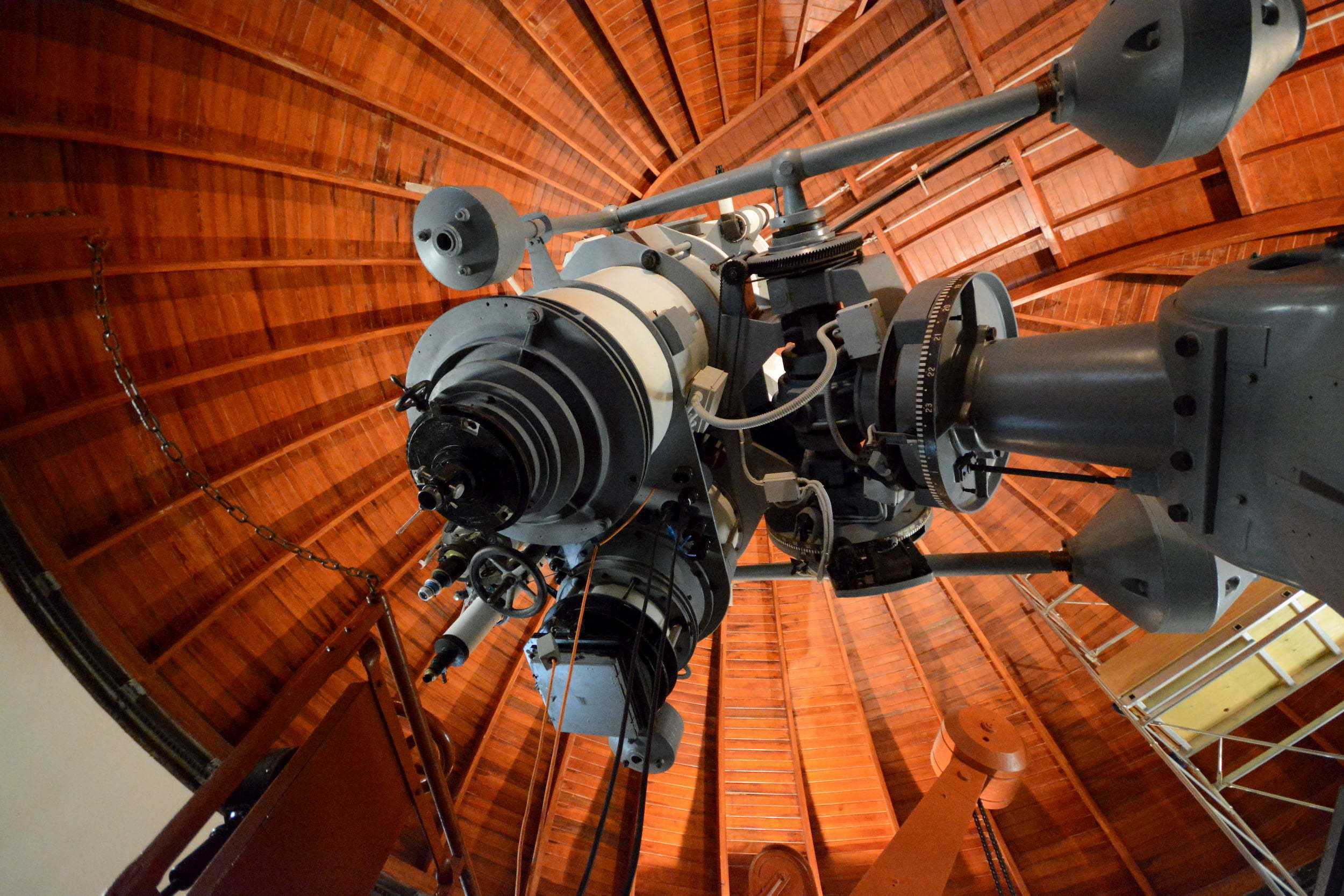

The Zeiss Double Astrograph at Castel Gandolfo © Vatican Observatory

God lets us learn without doing our homework for us

You also speak of primary and secondary causality. So who came first: God or the universe? Who or what causes whom or what?

This is one of the major questions that divides the “people of the book” – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam – from other religions.

In Genesis (part of “the Book”), its cosmology in the sense of how the universe is arranged is what the Babylonians understood; it was the best cosmology of the day, when Genesis was written. But of course it was obsolete even by the time of Aristotle. What is new and unique to Genesis is not what it says about how the physical universe is arranged, but what it says about the God who is responsible for it.

The Babylonians and the Greeks and the Romans all talked about gods within nature. But Genesis has only one God, who is there “before” there is creation. And I put the “before” in quote marks because God in fact creates space and time itself, so the “before” really means outside. That’s what we mean by “supernatural.”

As Rabbi Jonathan Sacks has argued in his book, The Great Partnership, it is the supernatural nature of God, ‘the discovery of God beyond the universe’, which is new to Genesis. It lets us see Creation as being different from, while encompassing, Nature (a distinction made explicitly by Pope Francis in his encyclical Laudato Si’).

The Creator does not serve as a replacement for the laws and forces of nature, throwing lightning bolts on a whim. Rather, this Creator becomes the One who accounts for the existence of such laws and forces in the first place. It also means, from a theological standpoint, that one cannot always see the will of the Creator in each individual event that occurs in Nature. But one can learn to know the personality of the Creator in the timeless, elegant, and beautiful character of the laws that underlie Nature and give it the freedom to act in ways that are good or ways that are not good.

So why would you “need” humankind? God deliberately leaves the Earth imperfect – why?

God does not “need” humankind. But God does choose to create humankind and place us into this universe, with the ability to be aware of its existence, and God’s existence, and the freedom to choose to love or withhold love, to exploit or to care. That freedom is an essential part of the human experiment. It allows us to love God, since love always has to be a free choice.

In connection with this, you give a remarkable keyword: “God's self-restraint”. I think this view makes God more and more human, a teacher…

All our images of God are just metaphors, of course. Some work better than others, some better for some people than for others. For example, the image of God as Father works great if you had a wonderful father, like I did, but it can get in the way if your father was not a good person.

The essential point behind this image – as a father, or a teacher – is that God is someone who points us in the right direction and gives us a start, but then lets us learn without doing our homework for us. For one thing, that would rob us of the pleasure of learning. It would rob us of the freedom to make choices. And it would rob us of the chance to grow into creatures who can see God face to face. As C. S. Lewis so beautifully put it, how can we meet God face to face till we have faces?

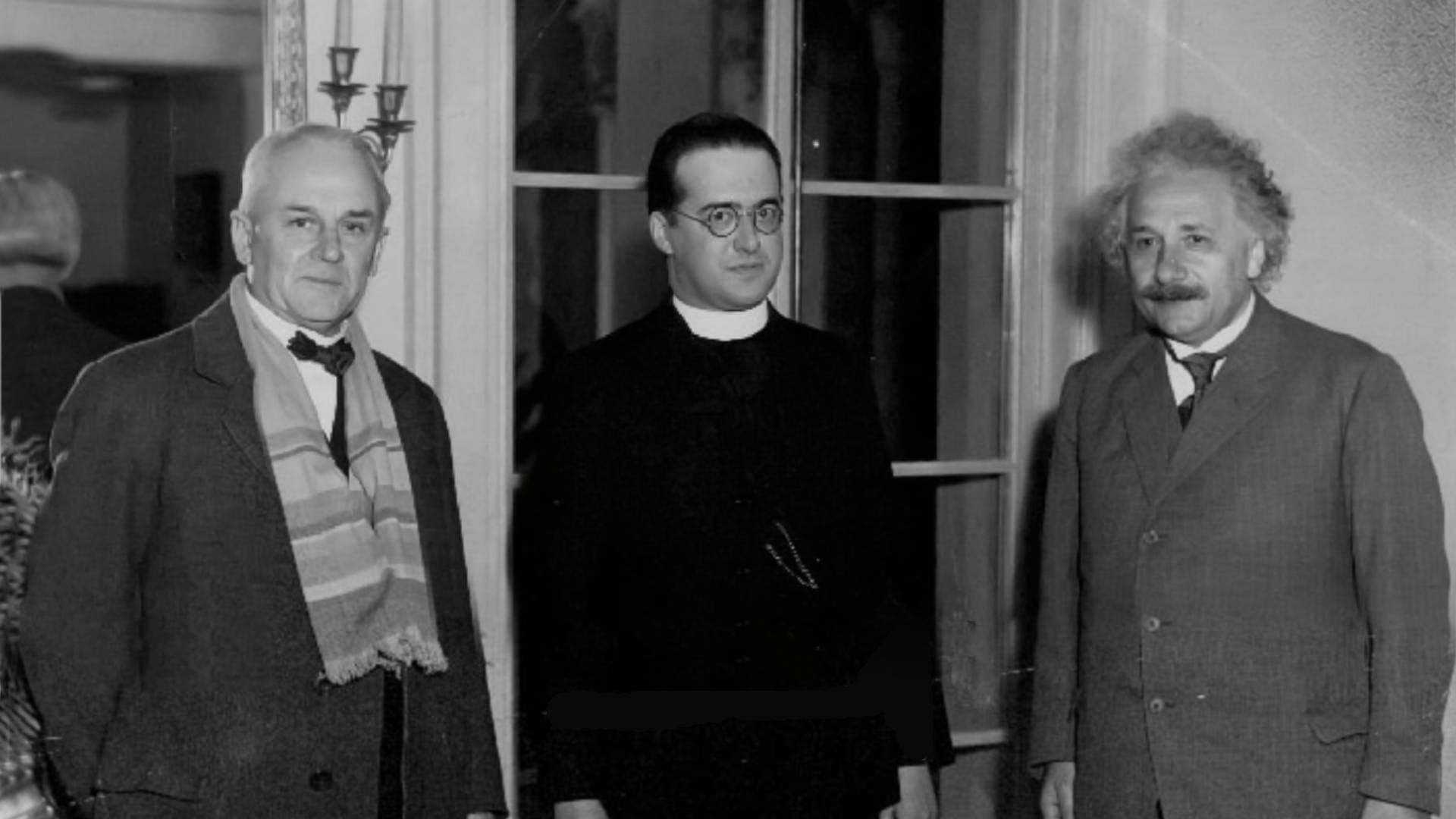

Robert A. Millikan, Fr. Georges Lemaître and Albert Einstein © Vatican Observatory

Science is a terrible thing to base your religion on

So is God part of the universe? Or outside the Big Bang?

As I have explained, God exists super-naturally, outside of creation. That’s what gives creation the chance to have meaning (vide Wittgenstein). But God also enters into creation, so that we inside creation can be able to find God and encounter God. (The more Biblically literate of your readers can probably cite the chapters and verses that are my source for these ideas; they are hardly original with me!) We Christians say that this has explicitly happened in the Incarnation. But I also see God in the beauty of the universe and the elegance of the way it behaves, what we call the laws of science.

Since you bring it up, let me point out something important about the Big Bang. First, in case you forget, the scientist who first came up with the idea we now call the “Big Bang”, Georges Lemaître, as it happens was a Catholic priest. And he insisted – to the Pope, no less – that what his theory described was not the same as the biblical creation from nothing.

First of all, the Big Bang depends on the existence of space and time and the laws of nature; it uses those laws, it did not create them. Second, it’s a human theory; the best we have at the moment, but nonetheless subject to testing and correction and maybe, even someday, being replaced by a better theory. And finally, if that day comes when we have a better theory, it will happen because the theory itself showed us the way to a better theory.

Indeed, the more important a scientific result is, the more that it will inspire scientists to go beyond that result. Science is in the business of making itself forever obsolete, and forever new. Which makes science a wonderful activity that will never lose its freshness. And it makes science a terrible thing to base your religion on.

And extraterrestrial beings? What do angels or demons in the spheres of the universe have in common with the so-called Martian in space?

If they exist in our universe – which we don’t know for sure, though I would be surprised if they don't – then our current cosmological assumption is to presume that they follow the same laws of chemistry and physics as we do. Thus, likewise if they have intellect and free will, they’d also be subject to the same tests of self-awareness and the freedom to love or hate, the same “laws” of ethical behavior.

That doesn’t mean that their relation to God has to follow the same pattern that ours did. After all, in our religious legends, angels did not have God becoming incarnated as an angel. But the fact that we can talk about angels and demons, be they literal fact or the best poetry we can come up with to describe what is otherwise indescribable, that shows that our faith has no foolish idea that God only made me.

The American humorist, Walt Kelly, put it well. He noted that some people say that there are more intelligent beings in the universe than humans, while others suggest that we humans are the most intelligent beings in the universe. Either way, he concludes, it’s a sobering thought!

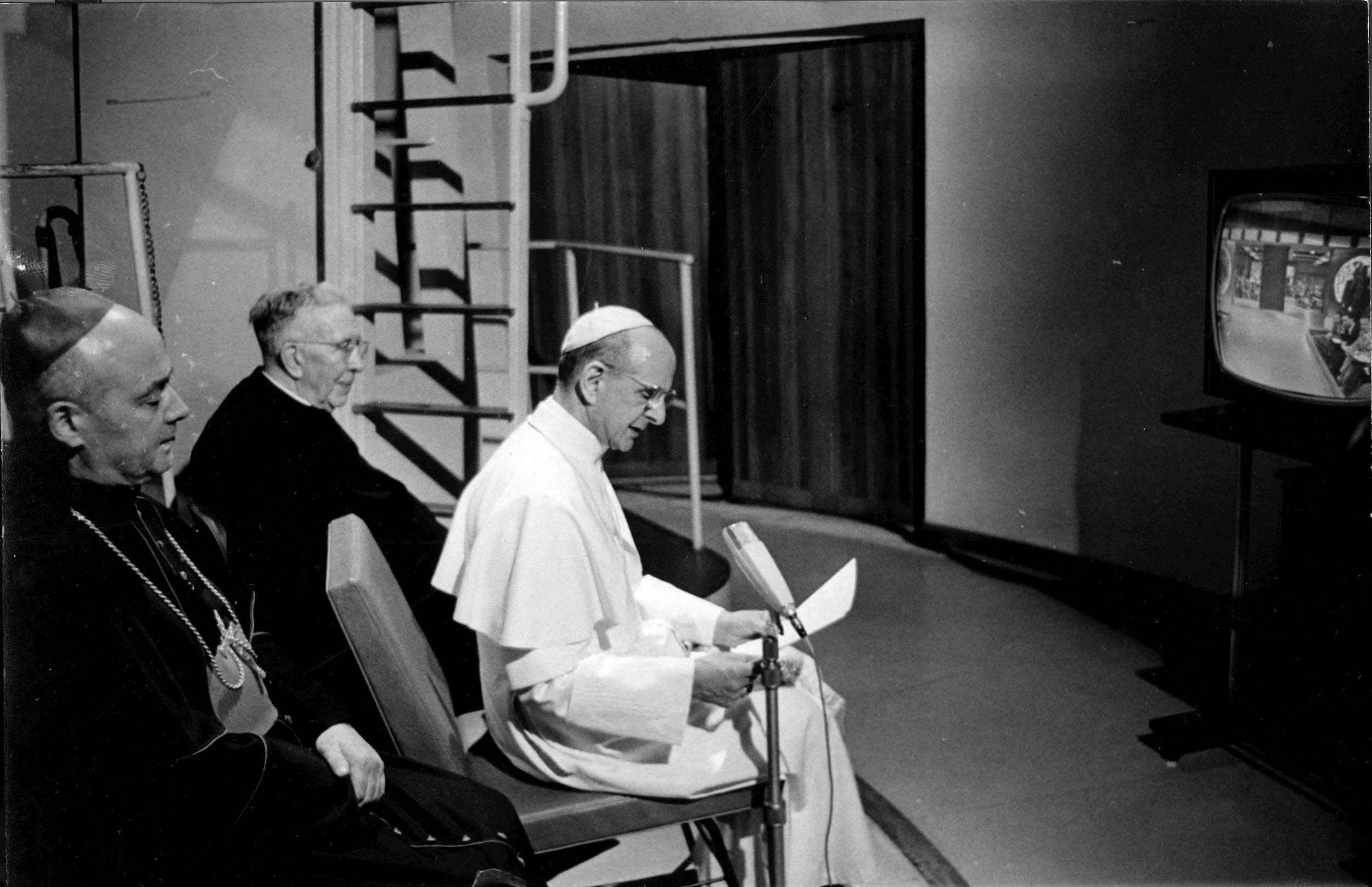

Pope Paul VI watching Apollo 11 moon landing on TV and giving an address and blessing to the astronauts, Castel Gandolfo, July 21, 1969 © Vatican Observatory

We are created to contemplate the beauty of the universe

What period does the Genesis come from and how advanced was the science of astronomy at that time?

I mentioned before that the timeless message of Genesis is not in the cosmology it describes. That kind of cosmology is science and science can never be described in a timeless way, since our science is constantly growing. (Do you learn Newton’s laws from reading Newton’s original Principia, or from a modern textbook?)

Rather, what is new and timeless in Genesis is in what it says about the God who created that cosmos. We learn (“In the beginning, God …”) that God already exists at the beginning, independent of creation. Unlike the Babylonian gods whose universe happened by accident, God chooses to create (“Let there be …”). The first thing created is Light – different from the Sun and Moon, by the way – indicating that nothing is done in the dark, it’s all open to be seen if you want to look. And God creates in an orderly way, as regular as day follows night.

The most remarkable thing about this creation is its endpoint. The Babylonians thought that the apex of creation was the city of Babylon. But in Genesis, the final creation, the point it is all leading up to, is the Sabbath: the day when we take a pause in our quotidian tasks and have the chance to contemplate the universe – how it is made, how beautiful it is.

We are created to absorb and appreciate that beauty. That’s what is meant when we are told that we do not live by bread alone. We spend our Sabbath in the creation and contemplation of art … or prayer … or dance … or sports … or poetry … or astronomy …. However we do it, that is what we are made for.

You quote the American Jesuit and astronomer George Coyne, director of the Vatican Observatory from 1978 to 2006: “In us, the universe has become self-aware.” What does that mean?

Each of us is a piece of the universe, with that ability to be aware that we exist and the ability to look around at where we are. It doesn’t matter who we are, where we live, when we live. The “us” that George refers to includes any entity that is capable of doing that looking around, on any planet, in any dimension – all such entities, from the humblest peasant to the most brilliant scientist, all equal in the eyes of the universe and its creator.

When I lived in Kenya (where I taught for a couple of years with the US Peace Corps) one of my great joys was to bring my little telescope to the villages where my fellow volunteers were living and set it up at night for everyone to look through. Everyone loves to look at the rings of Saturn.

Planetary Nebula NGC 7293, the Helix, 2004, VATT image © Brucker, Consolmagno, Romanishin, Tegler

The mission: to do good science – and show it to the world

The Vatican Observatory researches and teaches both in Castel Gandolfo, the summer residence of the popes south of Rome, which has had one of the oldest observatories in the world since 1578, and in Tucson, Arizona. How many employees does the Vatican Observatory have in total and how are the areas of responsibility and research focus divided between these two poles?

You can go to our web sites vaticanobservatory.va and vaticanobservatory.org (they are different sites, check them both out!) to get an idea of what we do.We have those two locations, plus all the other places where our adjunct scholars work. But we are one Observatory, with one overall mission: to do good science – and show it to the world.Today there are a dozen Jesuit priests and brothers who are full-time astronomers at the Vatican Observatory. We all have doctoral degrees in astronomy from the same places as our collaborators around the world – Padua, Arizona, Oxford, Toronto, Paris, and more. We each have our own research programs. These range from cosmology – the elucidation of the mathematics of quantum gravity – to the study of meteorites and dust hitting the Earth.Our annual reports (https://www.vaticanobservatory.va/en/publications/annual-report) give a description of the sorts of science – and outreach – that we do every year. Along with the dozen Jesuits they include reports by other scientists who work alongside us, including a dozen “adjunct” astronomers. These adjuncts are folks, all approved by the Vatican, whose work complements what we do. Though a few of them are also Jesuits, they also include lay people and members of other religious orders, men and women, historians and philosophers and theologians as well as astronomers.

Br. Guy Consolmagno © Marco Valentini / ESA

What role did and does the Vatican actually play in research and progress in astronomy?

A number of achievements are notable in the history of the Observatory since 1891. The first was the successful completion of its assigned zone in the Carte du Ciel photographic map of the sky. In the 1930s, the first systematic measurements were made of the spectra of pure metals, which led to the founding of the journal Spectrochimica Acta, which was coupled with extensive surveys of stellar spectroscopy such as the study of carbon stars. More recent work has included the color photometry of stellar clusters, trans-Neptunian objects, and near-Earth asteroids; spectroscopy of peculiar stars, and stars hosting exoplanet systems; and the systematic measurement of meteorite physical properties. Theoretical work in astrophysics has centered on the evolution of galaxies and the physics of the earliest moments of the Big Bang.

One pattern that can be seen in this work is that it often is centered on long-term (and often unglamorous) survey projects. These are of immense utility to astronomers but this work is often left undone because it tends to be difficult to fund, and not the sort of work that would bring attention (or tenure) to a given astronomer. Because the astronomers at the Specola Vaticana do not have to apply for grants to do their work or keep their jobs, they are free to adopt this sort of “orphan” science.

Is there any cooperation with the IAU or other astronomical organizations?

We all have collaborators among the astronomers at observatories and universities around the world. That matches our own personal backgrounds; we come from four continents, speak a dozen languages, and travel widely. My science has taken me to every continent, including Antarctica where I was part of a team hunting meteorites on the East Antarctic plateau. Because of this we often are called on to serve as referees at the journals where we publish and sit on panels that judge proposals from our fellow astronomers for funding from their national science organizations. It helps that the Vatican funds us, so that we don’t have to compete for those funds ourselves!We are also active in professional societies and organizations. Members of the Vatican Observatory have been officers of the International Astronomical Union (where the Vatican is a member nation), the American Astronomical Society and its Division for Planetary Sciences, the Meteoritical Society, and more.

The central role of religion in making science happen

What is the mission of the Vatican Observatory Foundation?

When light pollution around Rome made it impractical to continue doing astronomical observations from our site in Castel Gandolfo, the Observatory set up a remote office in Tucson with an arrangement to use the telescopes of Steward Observatory at the University of Arizona. However, at that time, Roger Angel developed a clever new way of making large telescope mirrors (melting glass in a spinning oven). He offered his first mirror to the Vatican if we could build a telescope around it. That telescope, the Vatican Advanced Technology Telescope, has been operating for thirty years now atop Mt. Graham in southeastern Arizona – a telescope made for the Pope with a mirror made by an Angel!

To pay for that telescope, its upkeep and upgrades and annual expenses, we set up the Vatican Observatory Foundation. It’s a nonprofit 501c(3) incorporated in the state of Arizona; donations are tax-deductible (at least for US donors). But of course, the first step of getting people to support the telescope is to let them know who we are, what we do, and why we’re worth donating to.

That public outreach is actually an essential part of any astronomical institution. It’s not just that it’s good policy to let the taxpayers (or other donors) know what they are getting for their money. It also taps into that deeper reason I talked about before, of why anyone does astronomy in the first place.

The “sabbath” things that celebrate creation are often things that we cannot do ourselves. I can try to paint pictures or write poetry that captures the joy in creation; but I can much more easily learn to appreciate paintings and poetry made by people who have been blessed with a talent for it. In the same way, hardly anyone gets the chance to actually do astronomy professionally. That means that those of us who do have that privilege, have the responsibility to share what we do with everyone else.

In our own case, there’s the added mission to show the world how religion can play a central role in making science happen.

Interview: © STERNENHIMMEL DER MENSCHHEIT / Teresa Grenzmann